When the smoke of the fire appears in the air, doctors encourage people to stay indoors to avoid inhaling harmful particles and gases. But what happens to trees and other plants that cannot escape the smoke?

They respond the same way we do, it turns out: Some trees close their windows and doors and breathe.

As atmospheric and chemical scientists, we study air quality and the environmental effects of wildfire smoke and other pollutants. In a study that began by accident when smoke engulfed our research site in Colorado, we were able to see in real time how the leaves of living pine trees responded.

How plants breathe

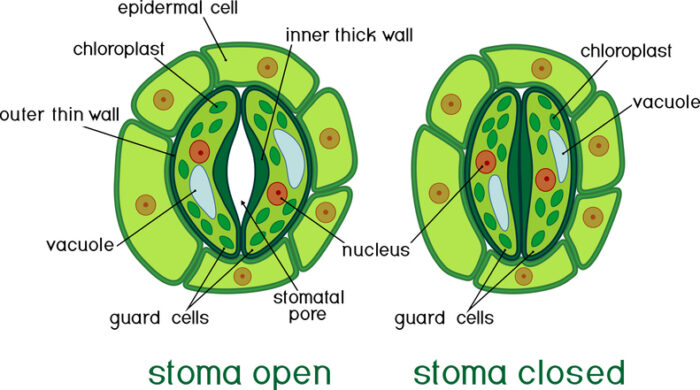

Plants have openings on their leaves called stomata. These pores are similar to our mouths, except that when we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, plants inhale carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen.

People and plants breathe in certain chemicals from the air around them and exhale chemicals produced within them – the smell of coffee for some people, the smell of pine for other trees.

However, unlike humans, leaves breathe in and out at the same time, constantly taking in and out of the atmosphere.

Data from over a century of research

In the early 1900s, scientists studying trees in heavily polluted areas found that those exposed to pollution from coal burning had black granules which close the pores in the leaves through which plants breathe. They suspected that the substance in these granules was made in part by trees, but due to the lack of materials available at the time, the chemical composition of the granule was not assessed, nor were the effects of plant photosynthesis assessed.

Most recent studies on the effects of wildfire smoke have focused on crops, and the results have been mixed.

For example, a study of many croplands and wetlands in California showed that smoke diffuses light in a way that makes plants more efficient at photosynthesis and growth. However, a laboratory study in which plants were exposed to artificial smoke found that plant productivity decreased both during and after exposure to the smoke – although the plants recovered within hours. a few.

There is some evidence that wildfire smoke can affect plants in negative ways. You may have tasted one: When grapes are exposed to smoke, their wine can become tainted.

What makes smoke toxic, even away from fire

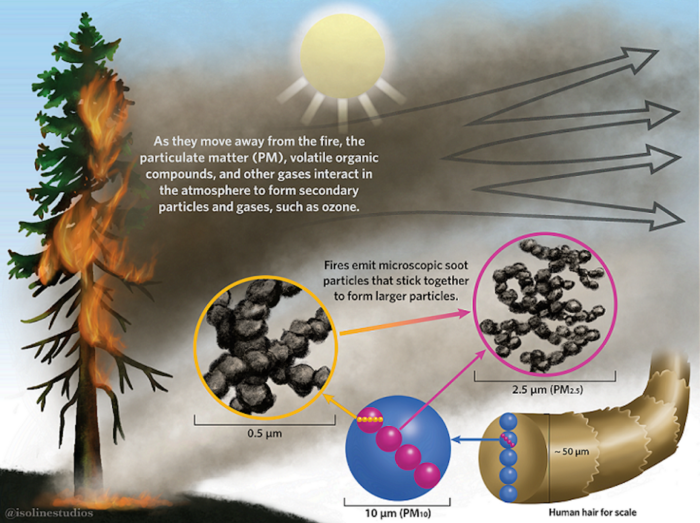

When wildfire smoke travels long distances, the smoke cooks in sunlight and the chemicals change.

The combination of organic compounds, nitrogen oxides and sunlight will cause ozone to become depleted, which can cause respiratory problems in humans. It can also damage plants by degrading the surface of the leaves, oxidizing the plants and slowing photosynthesis.

Although scientists tend to think of urban areas as the main sources of ozone that cause crops to decline, wildfire smoke is a concern. Other compounds, including nitrogen oxides, can also harm plants and reduce photosynthesis.

Taken together, studies show that wildfire smoke interacts with plants, but in ways that are not well understood. This lack of research is motivated by the fact that studying the effects of smoke on the leaves of plants living in the wild is difficult: It is difficult to predict wildfires, and it can be dangerous to be in a smoking situation.

Accident investigation – in the middle of a wildfire

We did not set out to study plant responses to wildfire smoke. Instead, we were trying to understand how plants emit volatile organic compounds – chemicals that make forests smell like forests, but also affect air quality and it can even change the clouds.

The fall of 2020 was a bad season for wildfires in the western US, and thick smoke drifted into our work area in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado.

On a very smoky first morning, we did our usual experiment to measure leaf photosynthesis in Ponderosa pines. We were surprised to find that the holes in the tree were completely closed and photosynthesis was almost zero.

We also measured the leaf production of their common volatile compounds and found a very low number. This meant that the leaves were not “respiring” – they were not breathing in the carbon dioxide they needed to grow and not exhaling the chemicals they normally release.

With these unexpected results, we decided to try to force photosynthesis and see if we can “defibrillate” the leaf in its normal rhythm. By changing the temperature and humidity of the leaf, we cleared the “air” of the leaf and saw a sudden improvement in photosynthesis and an explosion of organic compounds.

What our months of data have told us is that some plants respond to intense wildfire smoke by shutting down their exchange with the outside air. They hold their breath successfully, but not before being exposed to smoke.

We think of several mechanisms that could have caused the leaves to close the pores: Smoke particles could coat the leaves, creating a layer that prevents the pores from opening. The smoke could also get into the leaves and close their pores, causing them to stick together. Or the leaves may react to the first signs of smoke and close the holes before it gets too bad.

It is probably a combination of these answers and others.

The long-term impact is still unknown

The council still knows exactly how long-term the effects of wildfire smoke are and how repeated smoke events will affect vegetation – including trees and crops – in the long term.

As wildfires increase in intensity and frequency due to climate change, forest management strategies and human behavior, it is important to better understand the impact.![]()

Delphine Farmer, Professor of Chemistry, Colorado State University and Mj Riches, Postdoctoral Researcher in Environmental and Atmospheric Science, Colorado State University.

This article is reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the first article.

#Trees #Surprising #Response #Wildfire #Smoke #Scientists #Find