On the shores of Lac Bellevue, Alberta, Canada, Robert Tymofichuk approached two women sitting in lawn chairs. He had an unusual question. Were they worried if he launched his plane nearby?

After 1,800 hours of work, he was curious to know if it worked. With their permission, he climbed into the room with his wife, Shelley, and turned on the light. The engine, which came from a 1985 Toyota Celica, roared. The car shot into the lake.

“There is a danger because this thing can break through the water and sink like a stone,” said Tymofichuk, a teacher at the nearby New Myrnam School. A kilometer from the coast, he was tempted to cut the engine. “My wife is calling me. He says, ‘Robert, what are you doing, what are you doing?’ I’m like, ‘I’ve got to see if this thing floats.’ He says, ‘Not here!

They were far from the shore and the water was deep. He did the smart thing and listened to his wife, moving to shallow water. He cut the engine. The hovercraft floated away, flying in the sun and gentle breeze.

Love and Hovercraft

Despite their very cool name, hovercraft are not flying vehicles The Jetsons or Back to the Future: Part II. Instead, think of something like a boat that, instead of floating on water, rides on a cushion of air.

They are able to walk on seas, swamps and sandy beaches. That flexibility makes them ideal for the United States Navy and Marine Corps, which uses them to transport troops and supplies from sea to sea. For 40 years, Mountbatten’s giant plane carried passengers and cars across the English Channel.

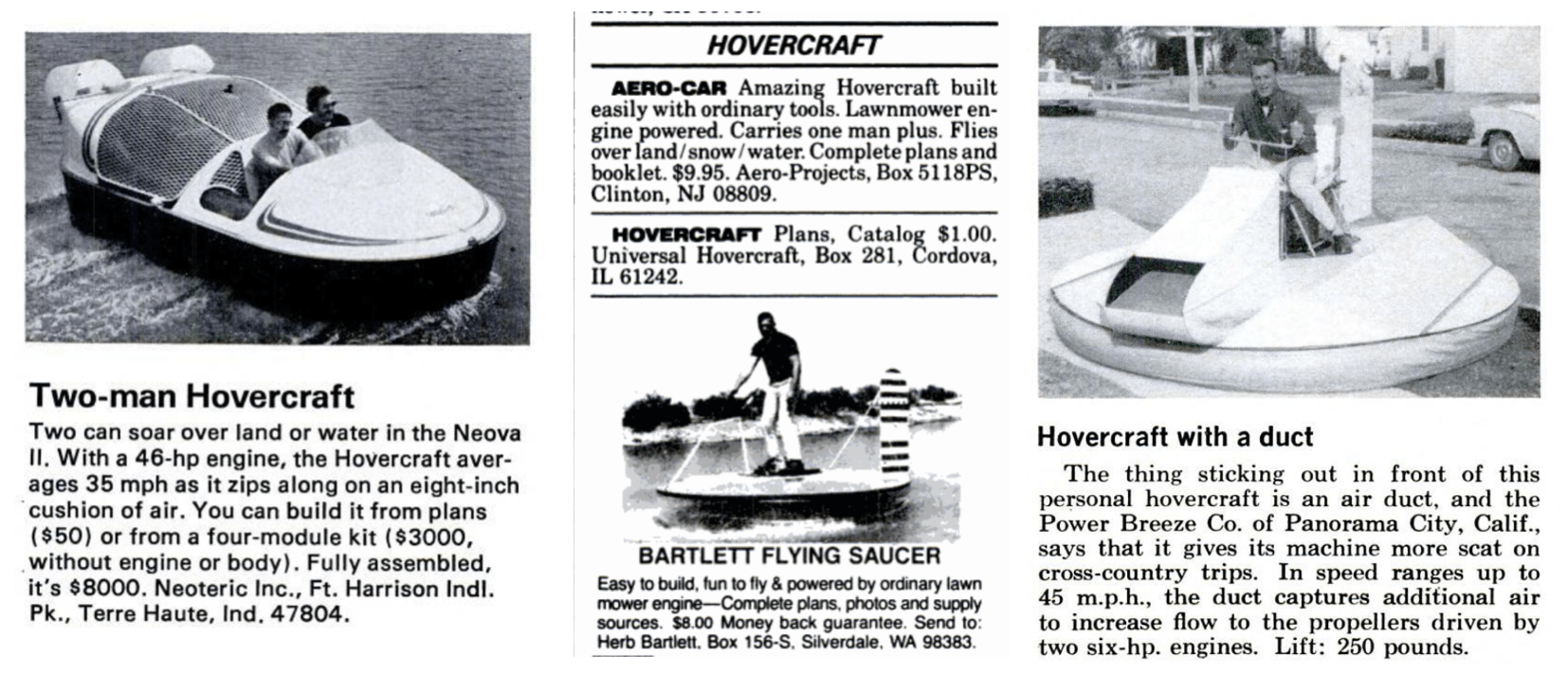

Tymofichuk fell in love with them as a child in rural Alberta. On his family’s small cattle farm, when he wasn’t fixing things, he was watching one of the two television channels, where he saw a segment featuring a hovercraft walking on water. He became emotional. While in eighth grade, Tymofichuk ordered a set of instructions from an Illinois company called Universal Hovercraft and began what would become a five-year project.

He remembers the day he finished building his first hovercraft in 1986. He said: “It was beautiful. His mother looked, the camera was ready. I started the engine, I it wakes up, nothing. He finally got it working. But over the years, he noticed a few flaws. It couldn’t carry much cargo or fuel which protects riders from splashing water and mud, and was unable to climb moderate trails. Tymofichuk repaired it in 2002 after a drought turned Lake Eliza into mud, exposing the skulls of the largest of the long-dead buffaloes, which the curious teacher discovered.

The next generation

Years later, he decided to build another hovercraft. In 2022, he posted a YouTube video, which now has over 100,000 views, documenting the entire year’s construction process.

The car is a hodgepodge of imported parts, such as a Toyota engine, which has been cut with extreme wiring to be as light as possible, and custom-made parts. He used discarded fiberglass found in an abandoned building. His wife sewed 107 pieces of rubber skirt, which attracts air under the car. For the joystick, he created a paper mache and covered it with fiberglass. Finally, he retrofitted a 1997 Jeep Grand Cherokee, adding a heater, ham radio, windshield wipers, and seats from a Volkswagen Jetta. The last thing? A shiny coat of bright red paint.

Tymofichuk isn’t the only uneducated scientist to have fancied a hovercraft. He followed the example of William Bertelsen, who rose to fame after the publication introduced his “wheelless car” in 1959. Back then, there was no eBay or Amazon to find sections from Reddit users seeking advice.

“If it wasn’t for the internet, there’s no way I would have built that second career,” Tymofichuk said. It made it easier for him to find specialty outfits, like Lone Star Hovercraft, that sell things he couldn’t find in auto parts stores. YouTube, where Tymofichuk has also posted videos of a DIY firewood and kayak with a battery-powered drill, is a valuable source of instruction for the hovercraft hobbyist. Tymofichuk raved about the videos from the Hovercraft Club of Great Britain, which holds six to eight races a year, where people regularly make impressive turns and can reach 80 kilometers per an hour.

Tymofichuk’s hovercraft doesn’t go that fast. It travels at a speed of 38 kilometers per hour on water, where it is relatively easy to maneuver, even in rivers with strong currents, and can slide over rocks, trees, and other obstructions more than eight inches above the surface of the water.

On ice, because there is very little drag, it can hit about 50 kilometers per hour. However, rushing into that situation is not a good idea. He said: “Imagine a car with the baldest tires in the world. Now imagine driving that car on ice. On a lake, in an emergency, a hovercraft pilot can I cut the engine and the car will land safely. Stopping on ice is a different story. It may need to be driven directly from Fast and Furious movie: fully rotate 180 degrees and engage to slow down.

Not that Tymofichuk is anywhere near driving skillfully. His hovercraft is best for leisurely, long-distance trips, such as the North Saskatchewan River, where he and his wife camp, pan for gold, and fish for sturgeon in remote areas. to reach them by truck or boat.

When I last spoke to him, Tymofichuk was spending his summer break helping with search and rescue efforts in Alberta, where wildfires have destroyed thousands of acres.

During the school year, she shares her passion for talking with students about STEM projects. They’ve built a sustainable greenhouse, converted a school bus into a tiny empty home, and restored a fleet of electric golf carts. He was awarded the Prime Minister’s Award for Teaching Excellence in 2022 from Justin Trudeau.

He said: “I’m trying to inspire the kids, to show them that if you want to make a hovercraft, you can do it. It’s just a matter of determination and determination.”

#teacher #spends #hours #building #childhood #dreams